Robert Jones: the best imaginable past and the lurking future

Copyright 2014, Filomena RosatiI was 18 when Robert Jones made one of the best photos of me ever created. He photographed me in a way that showed a side of me previously unseen and a personification I took on for the duration of my life. Half angst (sun in my face as I stood in a field in Sharpsburg, Maryland, suffering from allergies) and half earthbound, I looked like a model who suddenly found herself in a Mary Ellen Marks photo. The thing is, I never saw myself as a model.We were both at Shepherd College before such institutions took on terms like university. It was the time when we all photographed each other and thought we were so cosmopolitan.

Copyright 2014, Filomena RosatiI was 18 when Robert Jones made one of the best photos of me ever created. He photographed me in a way that showed a side of me previously unseen and a personification I took on for the duration of my life. Half angst (sun in my face as I stood in a field in Sharpsburg, Maryland, suffering from allergies) and half earthbound, I looked like a model who suddenly found herself in a Mary Ellen Marks photo. The thing is, I never saw myself as a model.We were both at Shepherd College before such institutions took on terms like university. It was the time when we all photographed each other and thought we were so cosmopolitan. Years have gone by since then and for a while Robert and I lost contact, but he reappeared about a decade later in my life. He was living in Texas then, working on a poignant series called “Looking Down.” It was such a relief to see he was still making images. And in that reconnection I learned a valuable lesson – he championed other photographers. He helped me deal with my own insecurities and showed me I did not need to always look at things in a vacuum – it was truly fine to enjoy work by others.He has continued to be one of my personal photo heroes and so I share this western-based (I think, he moves a round a lot it seems) photographer with you:

Years have gone by since then and for a while Robert and I lost contact, but he reappeared about a decade later in my life. He was living in Texas then, working on a poignant series called “Looking Down.” It was such a relief to see he was still making images. And in that reconnection I learned a valuable lesson – he championed other photographers. He helped me deal with my own insecurities and showed me I did not need to always look at things in a vacuum – it was truly fine to enjoy work by others.He has continued to be one of my personal photo heroes and so I share this western-based (I think, he moves a round a lot it seems) photographer with you:

Robert’s words:

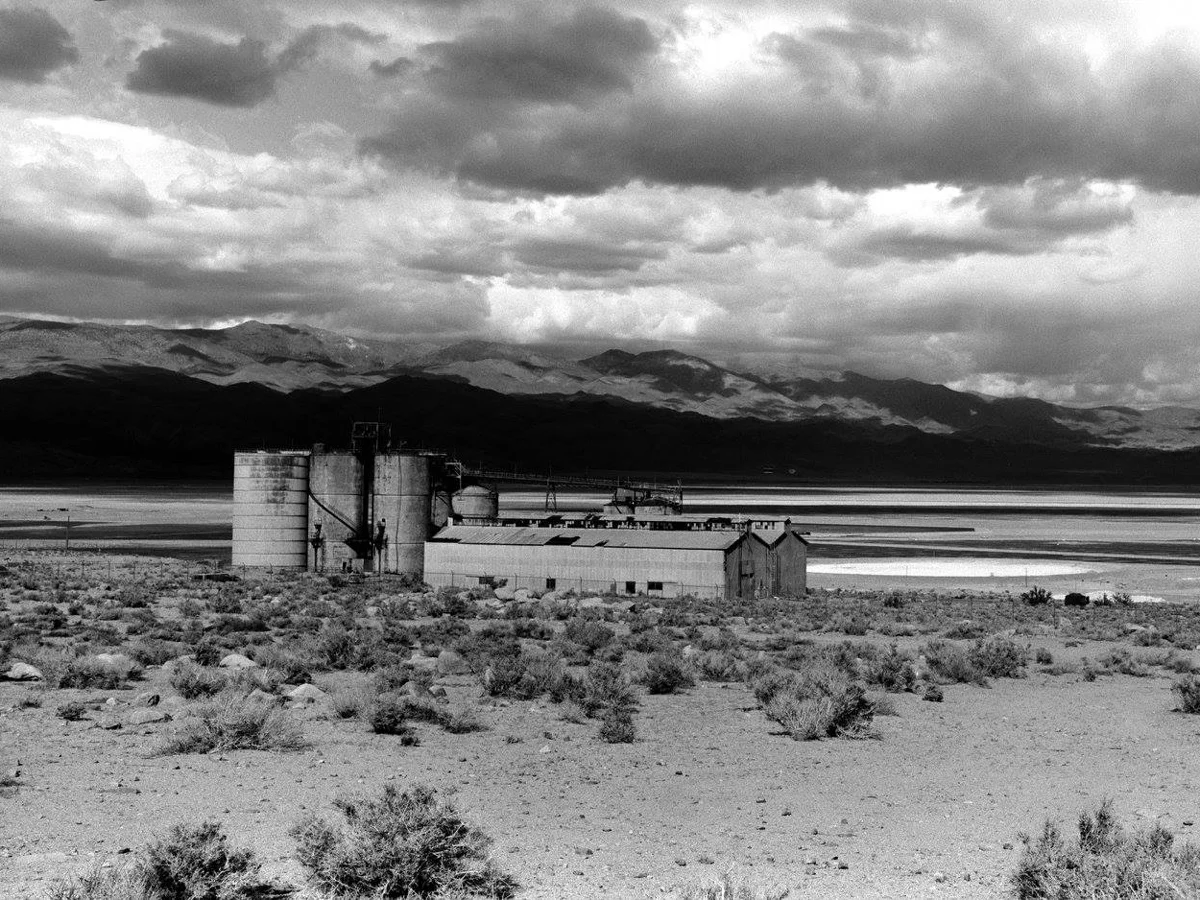

1. You were (and are) a fine art photographer, a commercial photographer and a military photographer. How does your work differ or tie together in these three different contexts?A. I have worked as all three, but it really is simply a matter of applying the technical knowledge I have gained over the years to three contexts. In the Army, I did editorial photography, and one of the changes I made as an editor within our unit is to assign photographers and writers separately to stories we were covering. That was not always possible in all instances, but in most, it afforded our writers the luxury of being able to concentrate either on photography, *or* writing – in the military, 46Qs are trained to do both. But that really downgrades the quality of a story, especially when you do not have much time to get it. When you're writing in your notebook, doing Q and A, and so forth, you're always thinking about the photos you're missing out on. And when you're shooting, someone brings up a point you need to remember to enter into your notebook, or some action happens you wish you recorded. So, I sent out teams of two photojournalists, and that really improved the quality of our content. Also, I was in the Army as it transitioned out of film to digital; by 2003, we were all digital. But, this was in a relatively primitive period in the advent of digital photography. So, I tried to get my camera to do what my Nikon film camera could, and it just was not capable of many operations, to produce the same level of quality. I still do not own a digital camera and am still a film shooter.As far as commercial photography goes, nowadays, I have not done much in that realm for a while. I need to rebuild my website and presence. No matter: I have been working on books lately. My background, originally, was fine art photography, and that informs me more than anything else. But, I am constantly experimenting with new films (yes, they still make them), and new methods of development.2. What do you consider your greatest accomplishment as a photographer?A. My greatest accomplishment has been being given the opportunity to mentor young photographers in the craft of film photography. Since the 1990s, I have mentored around a dozen photographers. A couple of them just wanted what I call "quick fix" solutions to problems they had, and I was happy to oblige. But, more recently, with the death knell of film and traditional darkroom printing being prematurely reinforced in the media, it takes a special type of photographer who wants to progress in photography, yet work against the grain – to take their time.I have been mentoring a young photographer in her twenties for about five years now. She reached out to me because of my knowledge of Polaroid photography. Yet, for the past couple of years, I have noticed how tireless she is in experimenting with different films, processes, and camera equipment - she really is indefatigable. So, at some point over the past couple of years, I have been phoning her, and asking for advice. It's overjoying to take someone to that point.One example is the fine-grain developer I relied on for decades, Edwal FG-7, went out of production. So, I fell back on Agfa Rodinal for the slow films, but I wasn't satisfied with what I thought was overly grainy negatives. Aimee Lower had been getting some excellent results with Kodak's HC-110, so I tried it, and instantly knew this was the one, especially at a 1:100 dilution. That's just one example.I'm more into the "feel" of how something turns out, but she is quite OCD, so she reads the technical data sheets. I was having trouble with reciprocity failure with Kodak Ektar 100 C-41 film, so I called her from California to ask her advice, and she recommended Fuji Superia 200 – a consumer film you can still buy at the drugstore! But, I was blown away by its exposure latitude.3. In looking back at your education (any of it), what was the most helpful experience you had in your evolution as a photographer and why?A. Two experiences come to mind most readily: I took an intermediate course in black-and-white photography at Hunter College, in New York. The professor, Mark Feldstein, had one major concern: To make first-rate printers of his students. He was a stickler, but he also had a way of guiding us - he was tough, but also helpful and supportive.The other was a camera store manager in San Antonio, who's retired now. I was attempting to get the "perfect print" with traditional 35mm SLR cameras – and getting nowhere. No matter how slow the film, and how sharp and fast the lenses, I wasn't getting the acutance and level of detail I wanted in my printing. Floyd Waller suggested I was beating my head against a brick wall, and since that point, nearly 20 years ago, I have been a medium format shooter, mainly using the Rolleiflex SL-66 camera, but also the Hasselblad Xpan panoramic system.4. Do you have a preferred format of photography and if so what is it and why (color, B&W, digital, alternative, film, or any combination)?A. I find that, as I get into a groove with a particular project, the demands of each project push me in a different direction. I have been working on a series of grain elevator photographs since 1999, and I use the SL-66 with Agfapan 25 - very traditional, very austere, so I stick within those parameters. A series on the La Boqueria market in Barcelona will have me using a Nikon FM-3A camera with a very fast 50mm/f1.4 lens - it's all about the smears of color bokeh. I use the same camera with Kodak Tri-X for a documentary series I am doing on the water crisis in California, and how the farmers there are toughing it out.Presently, most of my efforts are going into a "widescreen" series of panoramic photographs I'm taking in California with the Xpan. This particular format is still largely unmined - so, I pretty much make up my own rules of composition as I go. The one "alternative" format I still use is shooting Polaroids.. I tried, and failed, to get something going with Polaroid transfers a while back, but in the process fell in love with just making snapshots straight out of the camera.5. If a young photographer asked you for advice on becoming a photographer, what would you tell him or her?A. It would depend on their motivation, which type of photographer they'd want to eventually become, and what kind of technical advice I could give them toward those ends. But, the one thing I would advise them of is to not fall into the trap of regarding "snapshot" as a dirty word. Because, what that does (and this is drilled into future "fine art" and "professional" photographers) is to sotto voce bootleg into their minds that they have to unlearn all their photographic instincts that they learnt naturally, starting as children, with snapshot cameras (or, now, with camera phones). Snapshot photography is the essence of the beginning of how everyone learns to handle a camera and make images. Yet, we are exhorted to dispose of all that innate knowledge - the instinct of what makes a good photograph - and to learn instead to shoot only on a fully "conscious" level. But, who feeds that consciousness? The tastemakers and the gatekeepers. Photography is the most rigid and unforgiving of the visual arts disciplines, precisely because of the clubby and provincial attitudes foisted onto newly minted photographers by those at the top. But, thanks to digital photography, these people are becoming irrelevant, mainly because of the sheer volume of new work out there.

To learn more about Robert’s work visit:

- www.robertjonesphoto.com

- robertjonesphoto.blogspot.ca

- Looking Down: Photographs From the Sidewalks of Hyde Park, Boston

- Garish: Roadside Color Polaroids